Brutalism and Beauty

Wikipedia defines Bru-tal-ism as: An architectural style of the mid-20th century characterized by massive or monolithic forms, usually of poured concrete and typically unrelieved by exterior decoration. (Fine Arts & Visual Arts / Architecture) an austere style of architecture characterized by emphasis on such structural materials as undressed concrete and unconcealed service pipes. Also called new brutalism.

Webster’s abridged definition of Bru-tal-ism: A style in art and esp. architecture using exaggeration and distortion to create its effect (as of massiveness or power)

Brutalism, in a nutshell, is a celebration of the naked. In architecture, when structure and finish are one and the same, it is truth made manifest.

There are four structural materials that can be left undressed in multi-story buildings: stone, brick, timber and reinforced concrete. Steel frame is not one, it requires fireproofing above one story. Amazingly, timber is more fire-resistant than bare steel. Concrete has no tensile strength and steel melts with heat, but together they are superior: reinforced concrete can stand tall, naked, and beautiful.

A steel skyscraper, is a veneer reiterating the structural framework enclosed in fireproofing. Mies’ Seagram Building (1958) is essentially a lie…or what one might call a reiterated truth. It is not the naked truth of his one-story Farnsworth House (1951).

It was not until 1904 that the first concrete skyscraper went up in Cincinnati (15 floors) and to this day the Ingalls Building by Ernest Ransome waits for Time to strip away its robe of European tradition and reveal its true Brutalist identity…the CBS (1965) and Trump Towers (2001) in NYC will have to get in line, as well as the World’s tallest Building (2004) 165 floors above the deserts of Dubai.

The Whitney Museum (1966) by Marcel Breuer on Madison Avenue in NYC would have been an excellent example if not for its stone cladding…but the interior is textbook brutalist. A reverse lie…so to speak. That same CBS Building is also clad in stone, by the same architect who did the brutally honest TWA Terminal two years earlier.

If Truth is Beauty, all Brutalist buildings should be beautiful, but they rarely are: bunkers, bollards, parking garages and boring prefabricated panels. Not to mention dark and gloomy. Of course, Hoover Dam (1936) and nuclear cooling towers are marvels to behold, but with a name like Brutalism you’ve got to be more than competent.

The chemical admixture that is concrete requires great care every step of the way from pouring thru curing. That attention, and the forces at play, should be apparent on the skin, including the pour lines. The formwork should also be in sync with the structure. Imprint and texture are important features in brutalist aesthetics.

The rough and ready finish is very forgiving, allowing untalented architects to take advantage. They come cheaper for bottom line developers, as do unskilled carpenters…good formwork cost money. The Modern Movement was also welcomed by developers for its stark, flat esthetics...embellishments cost money. The public, none the wiser, often gets stuck with unsightly buildings just to save a few bucks for the greedy.

Veneers that hide sloppy workmanship cost less than installing good formwork at the start. Furthermore, fake skins cover early signs of disrepair that can be seen if left exposed.

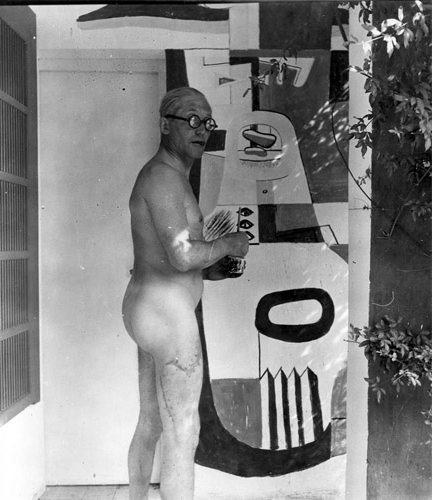

An educated society would not subject themselves to such indignities. However, the best workmanship is no guarantee to eloquence. Boston City Hall (1968) spared no expense but is a dark looming hulk compared to the lofty expressiveness of Carpenter Center (1964) and Gund Hall (1972). Perhaps it’s Corbusier’s ease with nudity that enabled him to master the medium like no other. His renditions of Brutalism are still unsurpassed.

Who would believe that 100 years after the Ingalls building, architects would still be masquerading concrete as steel? Brutalist sensitivities can extend to exposed wood such as the Ise Shrine. It is as old as the Parthenon due to a rebuilding ritual every 20 years…thus, rendering it more enduring than the temple to Athena atop the Acropolis.

The Gothic Movement eventually overcame its Barbaric moniker after centuries but within a generation Brutalism has gone from Roosevelt Island Soviet to National Mall Civic. It embodies the proverb that “in unity there is strength”. Concrete and steel working together toward a more perfect union…undressed and without the cloak of European tradition. Brutalism is truth unveiled and that’s a beautiful thing.

As an aside, it is materials that determine styles:

Trabeation (a.k.a. post and lintel), stone slabs as in the Parthenon, (447).

Arcuation (a.k.a. arches), brick as in the Pantheon, (126 AD).

Plastuation* (a.k.a. Shells), reinforced concrete as in the TWA Flight Center (1962).

There are movements within styles but fashion differs from style in that it’s fleeting…and appearance trumps comfort.